Seeing Layers of Meaning in Duke Chapel’s Windows

Visitors to Duke Chapel this holiday season may notice that two of the windows in the side chapel, the Memorial Chapel, are boarded up. That’s because the glass pieces for those windows have been removed for offsite cleaning as part of a five-year plan to finish a decades-long process of refurbishing all seventy-seven of the Chapel’s stained-glass windows.

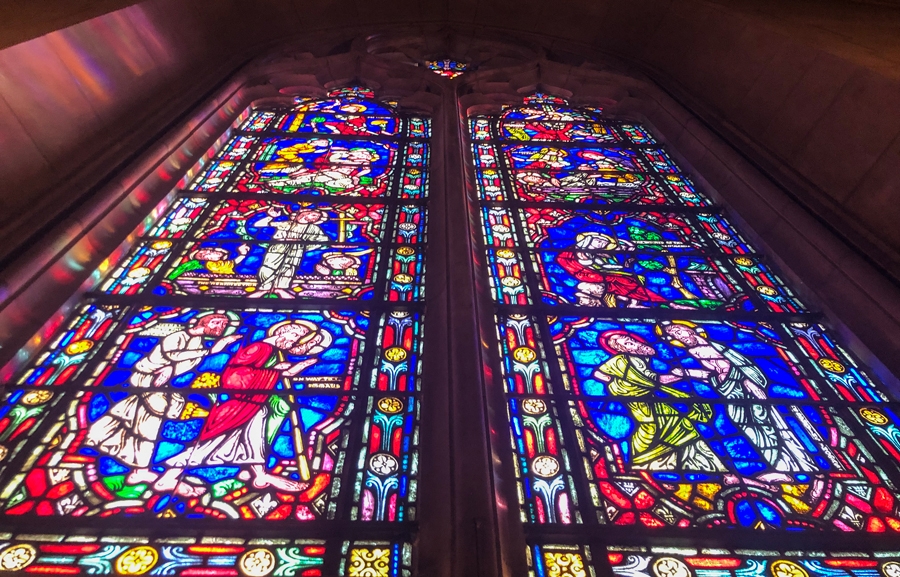

The most obvious effect of the windows is a general sense of awe that often causes visitors who step into the main sanctuary to look up, maybe snap a photo, and then pause to take in the majestic view of the vibrant and intricately designed windows.

That reaction points to one of the theological meanings of the windows, according to Dr. Anderson. He explains that there is a long Christian tradition of understanding church buildings as earthly outposts of heaven or the New Jerusalem.

The Chapel’s stained-glass windows comprise about a million pieces of glass. The large windows in the main sanctuary (the “nave”) depict biblical scenes from the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible) and New Testament, as well as saints and figures from the early church, using individual pieces of glass that are each one of seven colors— ruby red, blue, yellow, brown, white, purple, or green. (Yes, there is a “blue devil” tucked into a window behind the altar on the left.)

To delve deeper into the meaning of the windows, Dr. Anderson offers a simple approach.

In addition to reading top to bottom, the windows are meant to be read from left to right, starting with the windows immediately to the left upon entering the main sanctuary.

“The narratives of both the Old Testament and the New Testament start on the left and go in order up to the chancel area where the altar is, and then they come back toward the entrances,” he says. “So, there’s a vertical timeline, but there’s also a horizontal timeline.”

Dr. Anderson points out that the old style of stained-glass windows also finds a modern analog in our digital age.

A final aspect of the symbolism of the windows has to do with the properties of their colored glass.

“By the images being in the windows rather than painted on the wall, they have to be illumined by a light beyond themselves shining through them,” Dr. Anderson says. “In the traditions of Christian architecture, this speaks to an idea of special revelation—that these biblical narratives are truly perceived only as they are illumined by the light of God.”

“To see the windows is to be—symbolically or poetically—experiencing the loving grace of God,” he says. “They are not just illuminated, they are illuminating us.”