Bryan Stevenson Discusses Faith, Justice, and Shared Humanity at Duke Chapel

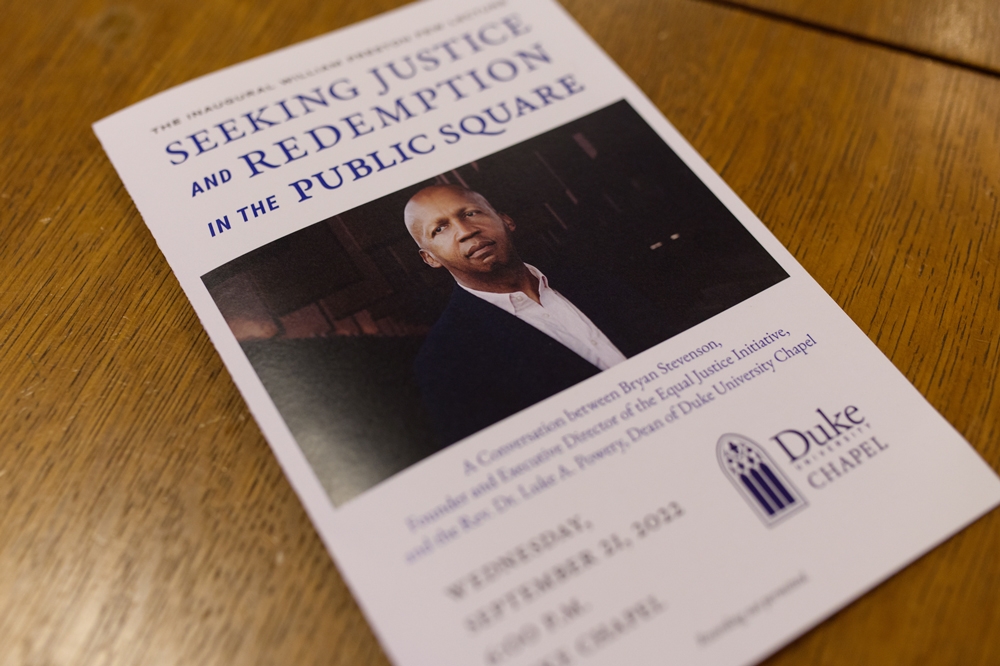

In a public conversation with Duke University Chapel Dean Luke A. Powery on Wednesday, September 21, the human rights lawyer and best-selling author Bryan Stevenson reflected on how faith and a sense of shared humanity have provided insights and motivation for his work in criminal justice reform.

“And what I want to talk to them about is that people are not crimes,” he said. “They can commit crimes, but they are not crimes.”

The event at Duke Chapel, titled “Seeking Justice and Redemption in the Public Square,” was the inaugural William Preston Few Lecture, which takes its name from Duke’s first president who articulated a vision of education promoting the courage to seek the truth and the conviction to live it. More than 750 people, who filled the pews in the Chapel’s nave, attended the event, while more than 600 people watched the livestream. No recording is available.

In introducing Stevenson, Dean Powery said Stevenson’s work is aligned with President Few’s vision of education aimed at producing students "made strong by the power to know the truth and the will to live it.”

A lawyer who has successfully argued cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, Stevenson said that mercy and faith are essential to his understanding of, and work towards, justice.

“It seems like every time I have had to deal with the weight of injustice there has always been a moment where mercy, where intervention, where grace, where redemption disrupted the weight of injustice and something happened,” said Stevenson whose best-selling book Just Mercy was made into a feature film in 2019. “I think that has been what has been essential to my career.”

In response to a question from Dean Powery about the role of faith in his work, Stevenson said, “To do the kind of things we all need to do to create more justice and more mercy and more equity and more opportunity, you have to be willing to believe things you have not seen.”

Throughout the hourlong conversation, Stevenson described a number of pivotal moments in his career. One came when he was a student at Harvard Law School, and he met a death row inmate for the first time while working for a nonprofit in Georgia. The man was so relieved to get the news that his execution was not imminent that he left the meeting with Stevenson, still shackled, singing the hymn “Higher Ground.”

“That was a moment when I knew I wanted to help condemned people get to higher ground,” Stevenson said.

“I was not only close to Bryan Stevenson in physical proximity but also in spirit,” Hines said, explaining that his biological father had recently finished serving a long prison sentence. Hearing from Stevenson, he said, “was an opportunity to receive further confirmation for how God wants me to serve those who are incarcerated and those impacted by incarceration.”

Another person inspired by Stevenson’s reflections was Christopher Wyrtzen, a Duke freshman. He said immediately after the event he went home and watched the movie Just Mercy, based on Stevenson’s book.

The event and film “showed me a lawyer who despite adversity, was able to rise up and defend those who weren’t defended properly,” he wrote in an email. “I am inspired to press through my education and journey to find my passion and area in life that I can further bless others.”

“That night was powerful for me because it made me understand myself and my struggle and to situate myself among the broken … just like I felt in that moment,” he said. “In fact, it is the broken among us that can sometimes teach us what recovery is all about—what redemption is all about.”

The point about recognizing a common humanity in others struck a chord with Phifer Nicholson, a divinity and medical school student who is also a theology, medicine, and culture fellow at Duke.

“I'd hope to model a similar form of accompaniment in medicine,” Nicholson said about Stevenson’s example of drawing close to his clients. “In both my theological formation and training as a future physician, I hope to likewise become proximate to communities at the margins, form meaningful relationships in community, and let my clinical research and advocacy work flow from the real connections that exist on the ground.”

Towards the end of the discussion, Dean Powery asked Stevenson about “working for justice, mercy, truth, redemption, love on this national cultural historical scale” with the opening in 2018 of EJI’s Legacy Museum chronicling slavery and racial inequality and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice with monuments to lynching victims.

Stevenson explained that during visits to South Africa and Germany he was struck by how those countries had public museums and monuments dedicated to telling the truth about atrocities in those countries—Apartheid and the Holocaust—but that the United States didn’t have similar institutions addressing the horrors of slavery, Jim Crow, and racial terror.

“You can't enslave people for two-and-a-half centuries and not talk about it or understand it; you can't lynch thousands of black people and cause six million to flee the American South and not address the trauma and injury that that created,” he said.

Reynolds Chapman, the executive director of the Chapel community partner organization DurhamCares, has visited the museum and memorial. Hearing Stevenson talk, Chapman, a Duke Divinity School alumnus, said he was newly inspired about his organization’s work to support people in Durham in caring for their neighbors in holistic ways.

“I think what made the event so special—and what makes him so special—is the way he sincerely and compellingly talked about things that are so often held at odds with each other today—justice and mercy, lament and hope, truth and reconciliation,” Chapman wrote in an email. “Bryan Stevenson is as far from shallow or cynical as any public figure I know, and I think that's largely because he does what he encouraged us to do—resist the politics of fear and anger.”

The Chapel’s community minister, the Rev. Breana van Velzen, sees how Stevenson’s message of hope resonates in Durham.

In concluding the event, Dean Powery said, “As you leave remember these words: people are not crimes. Go in peace.”

Stevenson’s two-day visit to Duke, September 21–22, was co-sponsored by the Duke Law School and Sanford School of Public Policy.

Photographs by Brian Mullins Photography.